Inducción de la enzima hemoxigenasa-1, que previene el daño en las vías respiratorias ocasionadas por la inflamación, podría ser utilizada como terapia. Director del Instituto Milenio de Inmunología e Inmunoterapia, IMII, dirige estudios sobre este virus, que es principal causa de infecciones severas del tracto respiratorio inferior en niños.

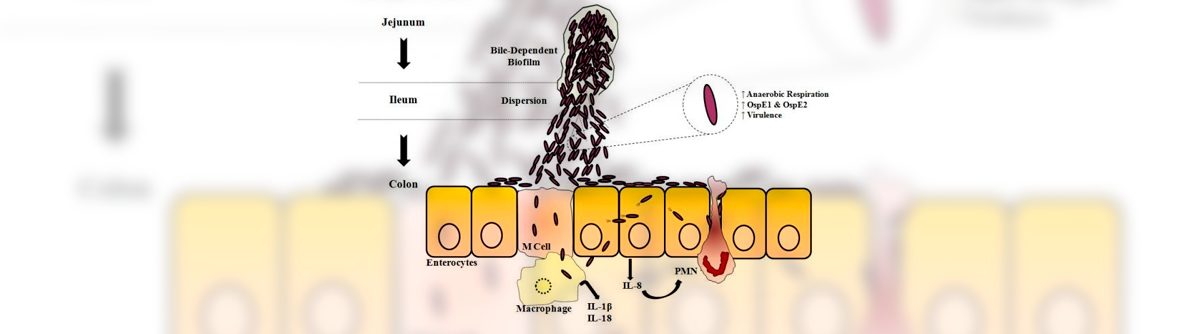

El desarrollo de nuevas drogas antivirales profilácticas y terapéuticas contra el virus respiratorio sincicial (VRS) es fundamental para controlar la carga de enfermedad en la población susceptible. Por ello, el Dr. Alexis Kalergis, académico de la Universidad Católica de Chile y director del Instituto Milenio de Inmunología e Inmunoterapia, IMII, examinó los efectos de una enzima, llamada hemoxigenasa-1 (HO-1), en la inflamación pulmonar inducida por este virus.“Los resultados de nuestros estudios muestran que después de la infección por VRS, la aplicación de HO-1 disminuyó la replicación viral e inflamación pulmonar de los modelos de análisis transgénicos. Además, observamos efectos antivirales y protectores similares. Finalmente, los datos in vitro sugieren que la inducción de esta enzima puede modular la susceptibilidad de las células a esta infección, especialmente las de tipo epiteliales, de las vías respiratorias”, señaló el académico.

Esta investigación puede complementar a la vacuna contra la enfermedad, desarrollada en nuestro país por el bioquímico, que se ha posicionado a nivel mundial con sus investigaciones y resultados favorables frente a esta afección, una de las que provoca mayor hospitalización y fallecimiento en menores de dos años. La aplicación de su antídoto ha mostrado seguridad y entregado resultados exitosos en un primer grupo de voluntarios.

La enzima se encuentra de forma natural en el organismo, expresada en muchas células y tejidos, sobretodo en el bazo, riñón e hígado. Sin embargo, también han descubierto que en ciertas patologías, sus niveles están disminuidos. Por esta razón, han podido explicar que la deficiencia de HO-1 en el organismo se asocia a un perfil “inflamatorio importante, y el desarrollo de patologías inflamatorias y otras de carácter autoinmune, como diabetes tipo I y Lupus”, afirma el Dr. Kalergis.

Los científicos del IMII llevan más de una década explorando la acción terapéutica de HO-1. Al respecto, el Dr. Kalergis señala que la enzima tiene capacidad para controlar la función de las células dendríticas, las cuales se encuentran desreguladas en pacientes con problemas de autoinmunidad, promoviendo una sobrerreacción en la respuesta inmune. ¿Cuál es el secreto de la enzima? Lo novedoso es que ésta libera pequeñas dosis de un gas responsable de la función antiinflamatoria. “Este gas funciona como un inductor de tolerancia. Y no es tóxico, ya que se libera en cantidades reducidas al interior de las células, y no a nivel sistémico. Su acción se da en la mitocondria, estructuras que controlan la cantidad de energía, y al hacerlo, las células bajan su nivel energético, lo que a su vez disminuye la actividad inflamatoria, fomentando así la prevención”, comenta el científico.

Virus respiratorio

El virus respiratorio sincicial, es de alta incidencia en todo el mundo. Principalmente en los inviernos y favorecido por el frío, contaminación y humedad, este microorganismo ocasiona bronquitis obstructiva, infecciones de vías respiratorias altas, así como neumonía en los casos más severos.

En Chile, el Estado invierte sobre 10 mil millones de pesos anuales en tratamientos, hecho que se suma al colapso de los sistemas hospitalarios. Por estas razones, el doctor en microbiología e inmunología estima que contar con la vacuna en el mercado “será de gran impacto en la comunidad afectada, en sus familias y también traerá beneficios desde el punto de vista económico, ya que permitirá prevenir los daños”.

Considerando que la mayor vulnerabilidad de contagio por el virus, ocurre entre los 0 y 2 años, la estrategia es poder aplicar el antídoto a las pocas horas de nacimiento del bebé. “El blanco principal serán los infantes y pensamos que con una sola dosis bastaría. Nuestra intención es llegar a reemplazar la actual vacuna de BCG, contra la tuberculosis y que la nuestra genere protección contra ambos patógenos”, señala el bioquímico de la Universidad Católica.

Patentes internacionales

En 2017, la vacuna recibió la concesión de la patente china. El profesor titular de la Universidad Católica de Chile, celebró este vínculo con el país asiático, gracias al cual “la vacuna ya cuenta con protección intelectual en esta nación, lo que abre paso a su comercialización y uso en beneficio de millones de personas”.

El antídoto también fue patentado en Estados Unidos el año 2013, con apoyo de un proyecto FONDEF-Interés Público, adjudicado por el científico y su laboratorio “Este hecho representa una contribución importante a resolver un problema de gran significancia para la salud pública mundial”, comenta el Dr. Kalergis.

Su trabajo está orientado a nivel molecular en reestablecer el equilibrio inmunológico en fenómenos autoinmunes. Gracias a la generación de la vacuna contra el virus respiratorio sincicial ha recibido reconocimientos internacionales como la Medalla de Oro para inventores que entrega la Organización Mundial de la Propiedad Intelectual (OMPI). El galardón, el cual se entrega desde 1979, destaca la importancia de los más de diez años de estudios del profesor titular de la Universidad Católica en relación a encontrar una vacuna para el VRS.

Además, realiza investigaciones enfocadas al entendimiento de los mecanismos moleculares responsables de la regulación de la sinapsis inmunológica y desarrollo de enfermedades autoinmunes, tales como la Esclerosis Múltiple, el Lupus Eritamatoso Sistémico y la Artritis Reumatoide.

El director del Instituto Milenio en Inmunología e Inmunoterapia, es Bioquímico de la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile y Doctor en Microbiología e Inmunología del Albert Einstein College of Medicine en Nueva York–USA, donde posteriormente realizó un post-doctorado.

Actualmente se desempeña como profesor e investigador en el Departamento de Genética Molecular y Microbiología de la Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas y en la Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad Católica de Chile.

A lo largo de su carrera ha publicado numerosos artículos científicos en revistas especializadas de alto impacto y contribuido en la formación científica de decenas de estudiantes de pre- y postgrado en el área de la inmunología.